Suffering in Peace

Part One

On the shoulder of a road at the doors of Jerusalem, a stone’s throw from the West Bank, I got scooped up in a dust-coated compact car by an Israeli woman named Noa.

I had never met Noa. We emailed the night before off a forum for carpools to the Dhamma Pamoda Vipassana Meditation Center, about two and a half hours to the northeast beneath the Sea of Galilee.

Noa was reserved, but overtly soulful. When I slid into her passenger seat, I felt the gentle current of her being lap onto my shore. I was at ease, and off we went.

The best conversations drift – flâneur-like – free from limits. Just two minds open, curious, and unbound by topic or time. And in this way, Noa and I talked. And talked and talked some more. After all, we were on our way to meditate in total silence for ten full days. We had a few driving hours to kill, so let’s get it all out, we agreed. This was her fourth (fourth!) retreat. Once a year, each year, she’ll head north for the long sit. “My kids say I come back a better Mom.” And by the time we parked on the grounds of Dhamma Pamoda, I thought huh, those kids are loved and lucky — how much better could she be?

These retreats are about such minds – all minds, in fact – and creating constraints around them, designed to minimize distraction, prune external stimuli, and direct attention to the natural activity of inner experience. It asks for abstinence from drugs, alcohol, sex, harm, reading, writing, and music. Our phones, collected at the door.

This spirit of constraints extends to the separation of genders, too 1 — the retreat center's site plan accommodates this with a partitioned, symmetrical layout. And so, after check-in, Noa and I hugged goodbye. With her palms on my shoulders, she warmly wished me good luck.

And finally, Vipassana asks for an informal vow of "noble silence". This means: no communication with other students – by speech, gesture, or even eye contact – nor with oneself aloud. A proper mute one becomes, hollowed and left with only one’s mind.

This all may sound extreme. Experientially, it is. And maybe, too, I can credit an ascetic impulse and a decade of meditation practice for taking to it with such alacrity. But the reasoning, the wisdom for why? I assure you, extreme it is not.

On the first evening ("day zero"), some one hundred strangers met in the meditation hall for orientation. Afterward, the retreat officially began, and so too our observation of noble silence. I ambled out of the hall, hands joined arms behind my back, and found a gravel path along the boundary of the retreat grounds. A calm descended on me — what I was there to do felt sacred, baring, intentional, and positively reductive. I looked into the moonlight and considered what espousing a long introspection invites: on retreat or in everyday banalities, it really is just you in that noggin, that body, and you alone. And whatever goes on in that space you inhabit, solipsistic as it may seem, makes or breaks a life of peace.

So what is meditation, really?

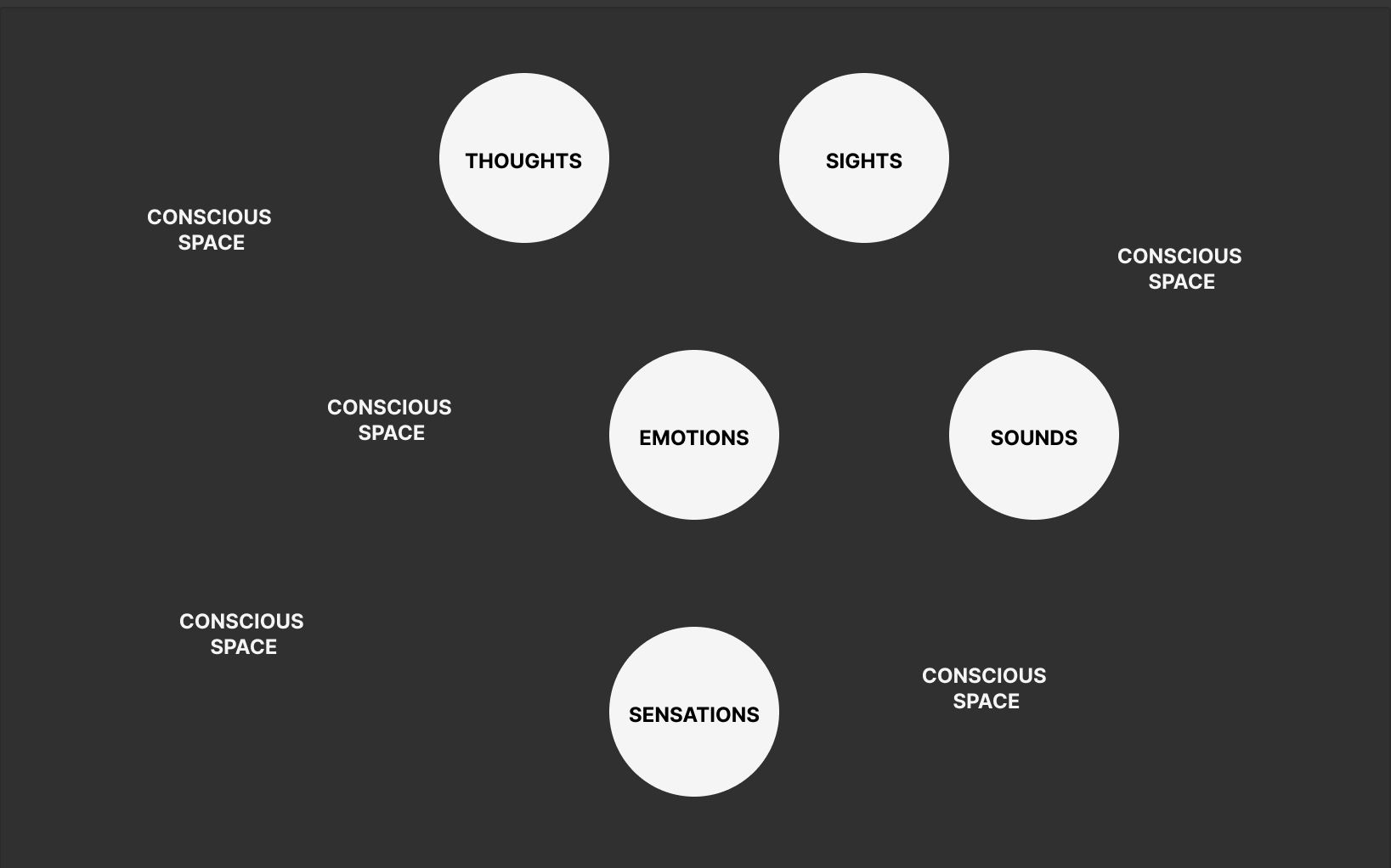

A basic instruction of meditation is to simply notice what shows up in your experience, without judgment, and rest your attention there. 2 I think folks who don’t habitually practice but have this understanding are still asking: Why does this matter? And I suspect they have yet to fully recognize that every waking moment is an ongoing navigation of the same five "content" categories of conscious experience observed in meditation:

- emotions

- thoughts

- sounds

- sights

- sensations in the body

There is literally nowhere else to experience oneself or the world — the activity of and relationship between these phenomena form our whole subjective perspective, inseparable from our environment.

Observing each category’s unique patterns, learning their rhythms, treating it all with great care, and seeing things for what they are — this is a road to a sort of mastery. And we conduct this process of self-discovery with the light of attention, by relaxing into awareness, in the practice of meditation. A training ground for being human.

The most common “object” of meditation we hear of is the breath — to observe natural respiration as it is, coming in, going out. That first round or two of breath may interest your full attention. But perhaps you notice the quality starts to short, like a flickering light, and you "wake up" in a thought about work or the weekend. Anyone who has tried to consciously pay attention to the breath for more than a few seconds realizes how futile the effort is. The mind is a circus!

Noticing the mind is perennially lost in thought is one of the earliest "breakthroughs" folks have in meditation. And it reminds me, in ways, of filmmaking. As viewers, we’re on the periphery of a simulated reality, yet our physiology responds as if "plugged in".

I recently watched Jim Jarmusch's Only Lovers Left Alive, a slow-burn story about two vampire-lovers with a refined taste for music, literature, and cinema. Having been alive for centuries, they’ve become erudite in their interests (imagine having hundreds of years to study a language or learn an instrument). And me, eyes glazed in a chair watching this play out on a two-dimensional screen, I am nonetheless absorbed, nearly grasping the ungraspable of having that kind of time to engage with culture, to stretch an average human lifespan. Phantasmagorical, the whole experience feels.

Thoughts function no differently, and often contain as unlikely a plot. In this theater of thoughts we sit immersed, the mind manufacturing a future that hasn't happened yet, a past forever behind us, or the imagination space itself – the realm of ideas – with Oscar-worthy directorial chops.

Once we experience this fact of mind fully, we’re humbled by our own insanity, and lightened by the same insanity shared by everyone else. Aha, you monkey! Only the present exists.

Even though the breath and thoughts get most of the attention when we hear about meditation, they are but two “objects” in that constellation of five distinct categories: emotions, thoughts, sounds, sights, and sensations in the body. Like furniture in a room, these categories are the “content” (furniture) and consciousness itself is the “context” (room).

Truly anything we can experience is a perfectly suited object of meditation, to simply notice and pay attention to. We can “zoom in” on one of these, like the sensation of breathing, or we can “zoom out” and fly over them, all in “view”.

If one pays close enough attention, their relationship to any object while meditating will move away from the personal, independent, and conceptual and toward the impersonal, interdependent, and abstract — just pure sensory data. 3 In my experience, there really is this sense of distancing that occurs, which relaxes one’s grip on, and one’s identification with, the objects of consciousness.

And with enough practice, one makes contact with a fundamental law of nature: it’s all impermanent, always changing. Every object just appears in its own place, does its thing, and then disappears. All in a single, unified space: the constant of consciousness itself.

It’s these shifts of awareness that swell the capacity of mind and produce tremendous psychological relief, the basis for why folks champion meditation. To relate to difficult feelings, anxious thoughts, or physical pain in this way? It’s a life-changing reframe. Over time, the mind habituates this wisdom into everyday you — the "tools" naturally pop up when applicable.

Speaking of “you”, there's a big question, which we won’t take on right now in detail but needs to be asked: if everything that one can experience in meditation is an object appearing in consciousness, is there a subject? Who, or what, seems to be paying attention? Who is the meditator? Where are “you” in all of this? Hint: it’s a trick question.

This is all to say that consciousness is a weird place where weird stuff happens, but it’s where all the stuff happens. And our task is to change how we see that stuff, how we confront it, how we react to it. We just don’t know what’s over the horizon if we do – how “good” things can get – so we’d be remiss not to investigate. And investigating with gravitas is to go on retreat.

Part Two

Suffering in peace

Suffering, a bad word. Trembles the heart to see another in its throes, at times too intense to bear ourselves. And we lie in wait because it’s always here, the trapdoor to a haunted cellar. Suffering is at the heart of the human experience and, not coincidentally, of Vipassana too — an effort to break down what gives rise to this “universal truth”. A little less suffering in our world might mean a lot more peace.

It’s also a big word, used colloquially to describe the wake of big events. But in Vipassana, suffering is a broader characterization for any non-contented state of mind, states particularly devoid of “equanimity”.

There are moments – fleeting as they are – maybe a summer afternoon, nowhere to be, nothing to do. You’re on a beach, a light wind cools the sun’s heat in a way that makes your skin smile. That boat in the distance sails and so, too, your spirit. Elsewhere are emails, dependents, obligations. But this day will end and tomorrow you have what is sure to be a stressful one, the world is full of problems, and life is a strange, temporary, beautiful disaster. You meet this whole circumstance with acceptance, no strings attached, and are patently at ease. This is equanimity.

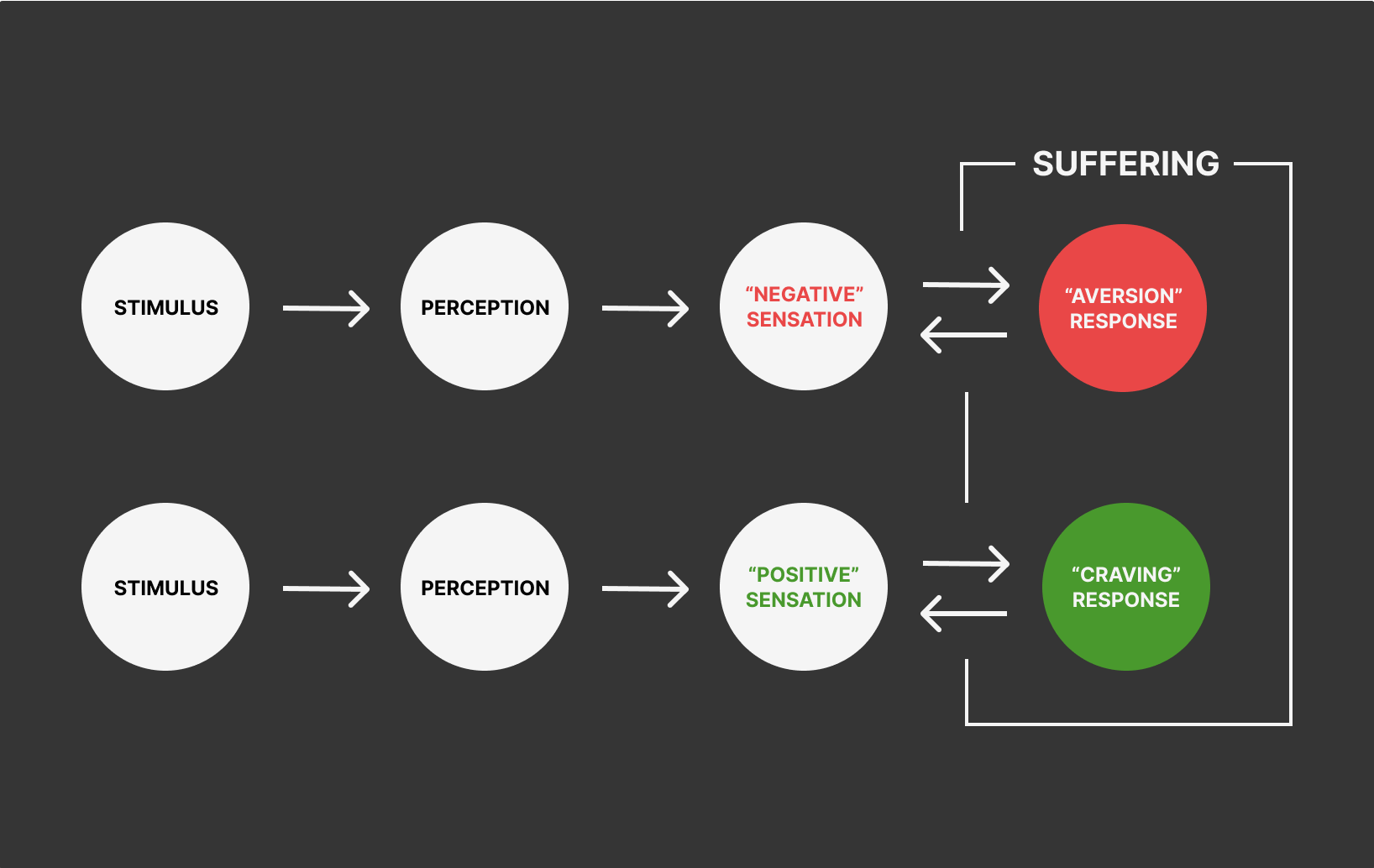

But, how often do we feel this way and not tossed around by it all? 30% of the time, if one is lucky? 4 Vipassana suggests the remaining 70% is a product of two primary psychological responses that produce feelings of suffering: craving and aversion.

When we don’t have something we want, we crave it, and when we have something we don’t want, we’re averse to it. When either is true, the mind and body naturally speak up, shout, squirm, and can make one want to put the ‘rum’ in tantrum. That craving and aversion can be indulged is merely a palliative. And we know this, but our innate wisdom gets overwhelmed by the forces of suffering in action: longing, frustration, desire, annoyance, impatience, anger, worry, and sometimes, a total freggin’ meltdown.

Responses like these have long been habituated — when we lose our keys, grieve the death of a loved one, see someone’s “life” on social media, reflect on a childhood memory, or wish the weekend wouldn’t end. With these examples alone, we can see the “gradient” of suffering on a spectrum, from a brief loss of control or trivial sense of lack in ordinary moments, to our private world burning during the most harrowing realities of human life. Suffering defies to be defined as one thing and crucially, has an amplifying ally in our capacity to think things dead.

And so we must learn to suffer well.

Vi-what-ssana?

I’m not a Buddhist historian, nor a Vipassana pundit, I’m just a psychology dork and systems thinker interested in tools. I went on retreat green and left ten days later with a sense I had acquired a psychological Swiss army knife of sorts, that the technique had managed to map the laws of mind in some fundamental ways.

It’s worth noting that Vipassana is not a dogmatic belief system requiring blind faith. It’s all about experiencing "truth" – if you will – by being present with the physiology of one’s own body. And while it makes some lofty claims around the “eradication of suffering”, “liberation”, and “enlightenment”, I actually think even a pragmatist wouldn’t shy away from this language as descriptors. But, and this is a big but: only after being known directly — to collapse the space between the intellectual and the experiential, between hope and proof, one must meditate, must go on retreat.

To call the structure of the retreat regimented would be an understatement. Morning bells echoed across the grounds each day at 4:00 am. That a wake-up call before dawn didn’t make me murderous was eased merely by the sense I was a part of something primordial, precious, and utterly bizarre. And so, I’d toss the blanket aside and rub the sleep out of my eyes as I hobbled to the meditation hall in the dead of night.

Between our wake-up call and lights out, we meditated for some eleven hours, punctuated by three breaks for meals and rest. That’s over one hundred (100) hours of meditation in ten days. I don’t think “accomplishment” is the right word here, but that sure is something.

Meals were vegetarian and served buffet-style, prepared graciously by humble retreat “alumni” who returned in service of new students, and to sit yet again. When not in the dining hall, I rested in shared living quarters, or sauntered along the retreat grounds among other students and the biodiversity of the bucolic north of Israel. Again, with no distractions and in complete silence. Soon enough, we’d head back into the hall for meditation.

This all may sound like one big torturous bore, like a ten-day prison sentence with decent grub and a view. And in a way, it was. So what the hell were we actually doing?

For an hour each evening, a video recording from the 1970s was screened to all students. It featured a Burmese man who popularized the Vipassana technique after its discreet inheritance within a small lineage of East Asian monks over two millennia, like a metaphysical heirloom. In the tape, he was leading a retreat in California and recorded it for distribution, as a way to create a standardized, consistent course experience around the globe. 5

At the orientation on arrival (day zero), we watched day zero of his California retreat. On day one of ours, we watched day one of his, and so on through the ten days. Chronologically and incrementally, he provides instruction, unpacks theory, and offers much commentary on the benefits of Vipassana, its history, and the nature of mind. I took all this with me onto the meditation cushion as navigation, but nothing fully prepares you for being out on the high seas of consciousness.

Wax on, wax off

The famed scene in Karate Kid where a wise Mr. Miyagi demands Daniel to repeat mundane tasks like polishing a car to indirectly teach him karate was a bit like the first three days of retreat.

We had been instructed to pay attention to the breath, but only insofar as it appeared in the space between the bridge of the nose and the upper lip. To observe, as closely as we could, air passing in or out of the nostrils, tingles above the lips, itches on the nasal bone, temperature on the tip — “scanning” for any sensation that showed up on this triangle-shaped surface area became the focus of my world for two straight days. If the mind wandered, I’d just note, now the mind has wandered, and return attention to the breath.

For day three, that “target” area was shrunk – unbelievably – to the small, concave patch of skin between the nostrils and the upper lip. A finger nails-width of space we were to spend eleven hours trapping all sensations with the net of attention, again and again and again.

Why were we doing this, you ask? Some students ran away by then, sped off in their cars, an answer to that question abandoned. The rest of us endured and, from the video recording of day three, came to learn, in fact, that we had been Miyagi’d by Vipassana itself: for those 30 or so hours of meditation, I had inadvertently been sharpening my attention with the focus of a maniacal craftsman, skilling it up, developing sensitivity to even the subtlest of sensations. Heck, if a cell divided in the tissue of my upper lip, I'd have felt it.

I couldn’t say with any degree of precision, but I’d estimate this refined dexterity with attention brought 10x more sensation into “view”. To be sure, these were sensations that were always there, but the quality of attention wasn’t honed enough to notice. Now, it was supercharged and readied for deployment on day four as we went deeper into experience.

The space between

On retreat, of course, one is still oneself while cross-legged on that cushion — flawed human, monkey-minded, an aging body. And so, at times it was a full-on suffer fest. The body screamed with pain in all the ways it knows how and continuously adjusted itself, hunting an untraceable comfort. And the mind, like a wild animal, fought restraint, fled to the imagination, boiled with frustration, and disobeyed requests for basic self-compliance. After all, one is forcing mind and body to do this thing they’ve never done, strapped to eleven hours a day of stationary meditation, like a psychological straight jacket.

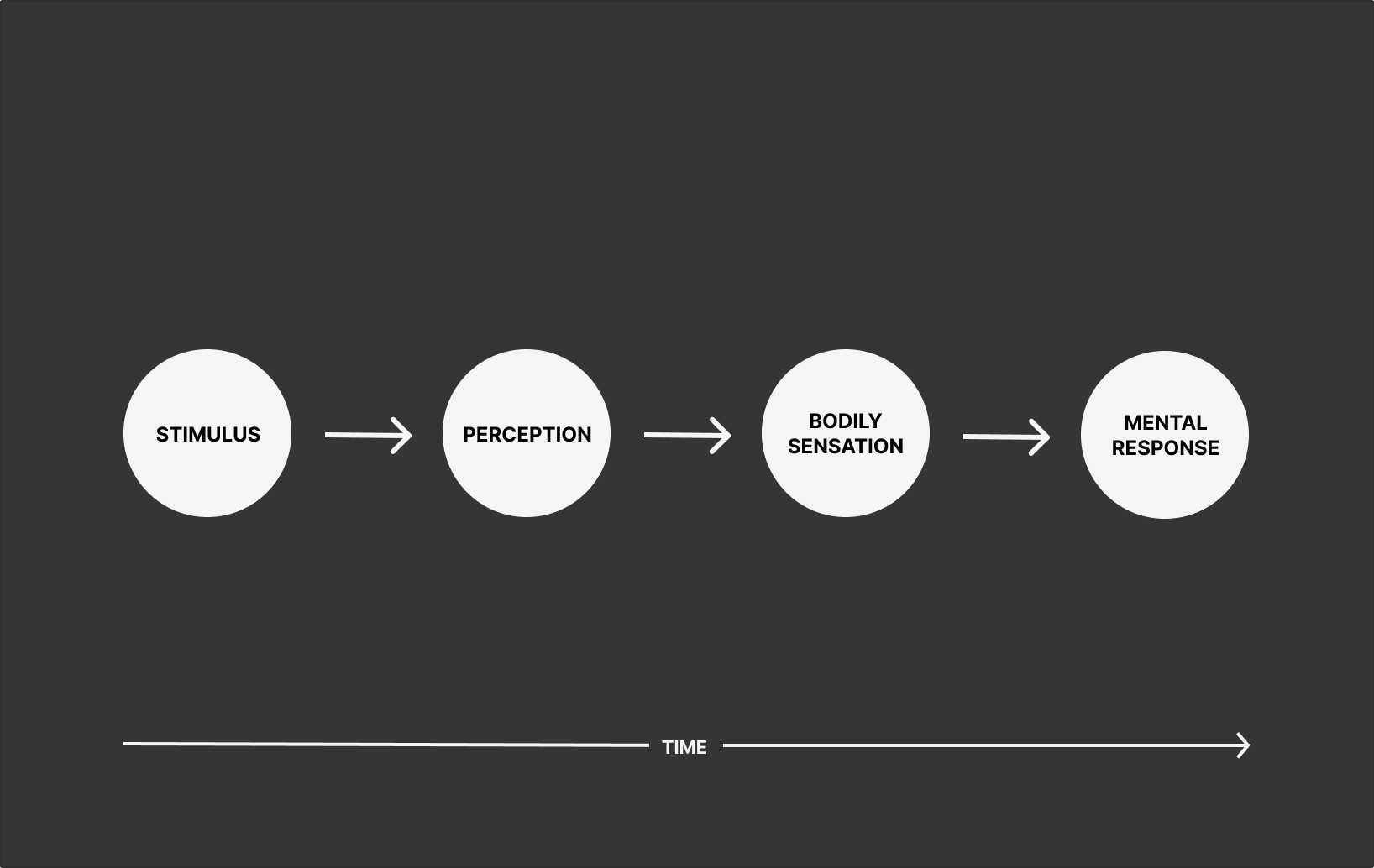

I’m reminded of the common dictum from Austrian psychiatrist and holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl in his Man’s Search for Meaning:

“Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom.”

Whether Frankl was influenced merely by his powers of analysis in witnessing the ineffable suffering of Nazi camps, by eastern wisdom directly, or by both, it’s this very insight, examined at an even deeper, more specific level, that became the project of Vipassana beginning on the fourth day of retreat.

To take a microscopic look at this process, we made a precise psychological incision with the scalpel of attention and inspected the very texture of experience itself. We were instructed to continuously scan the body, from head to toe and toe to head, ranging over every square centimeter of surface area. And to keep pace with every passing “unit” of stimulus-response (UOSR) wherever it appeared, spotlighting each one in procession. In doing so for some 55 hours over the next five days, their operative nature became increasingly revelatory, comprehensible, and intervenable.

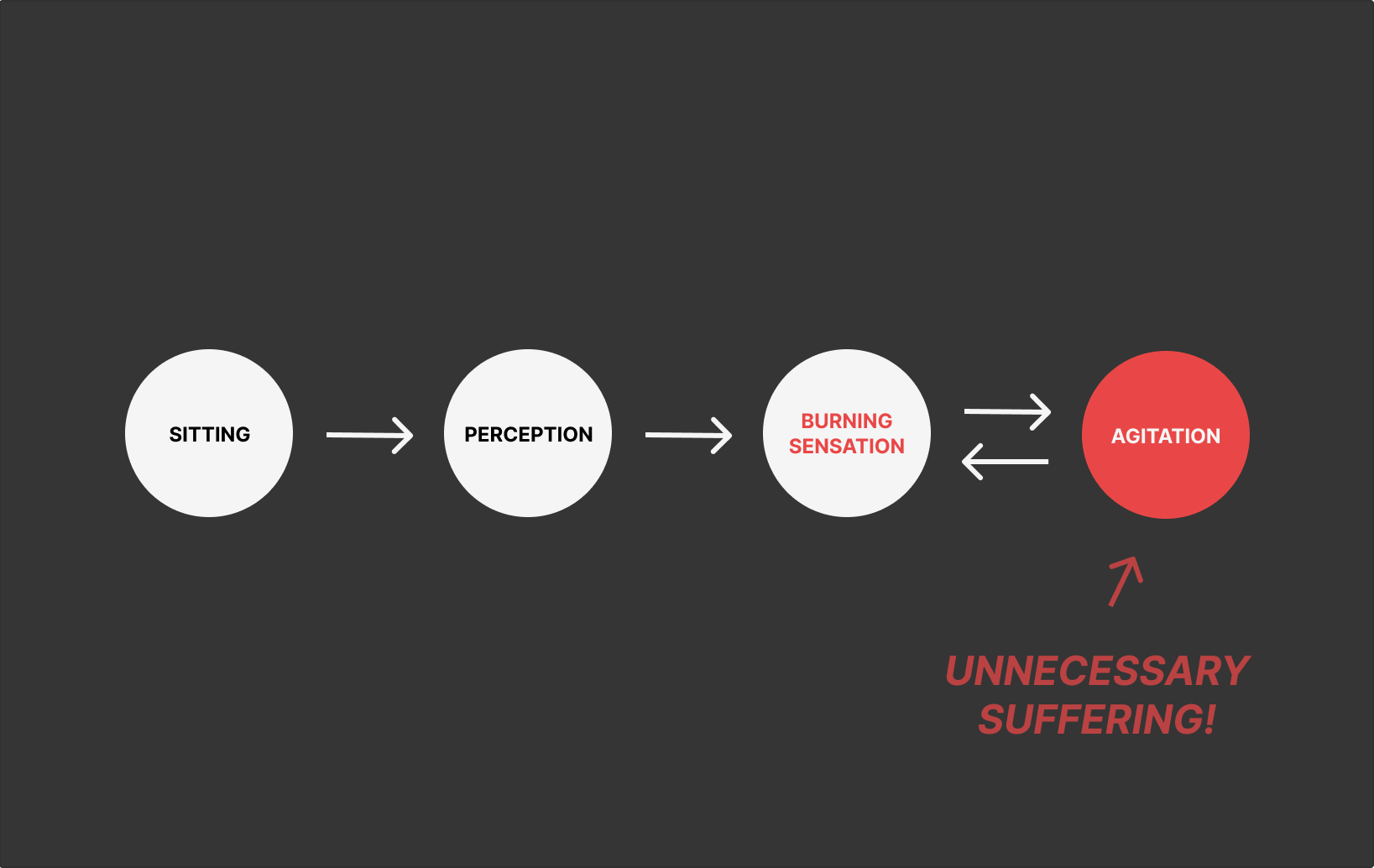

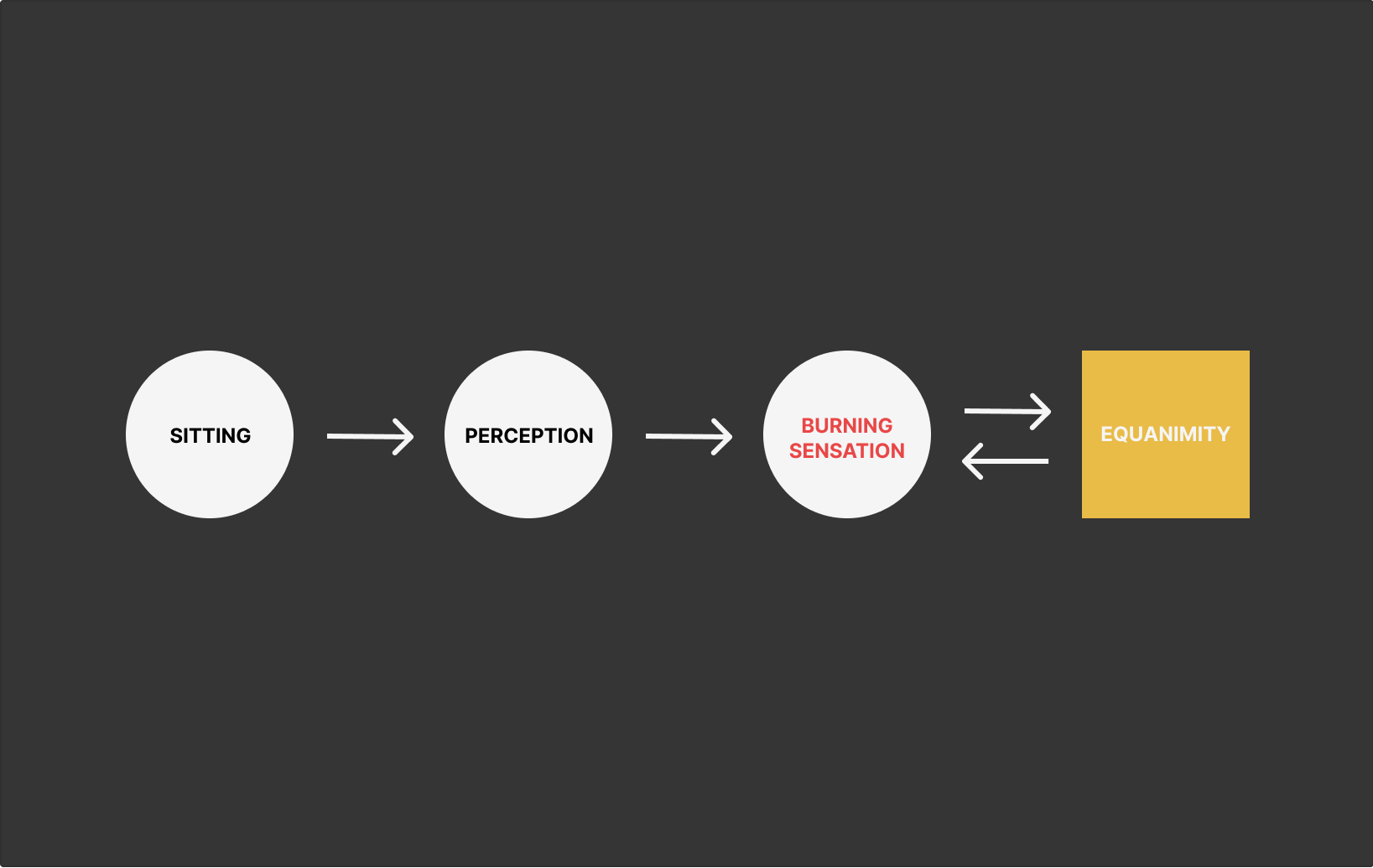

It revealed my reflex to respond to “positive” sensations with craving and “negative” sensations with aversion, 6 and how a signature of suffering would immediately follow as a consequence of that response. A burning sensation that would arise in the lower back from sitting cross-legged, for example, would provoke agitation in the mind, spawning a frustrated inner monologue of hurled expletives at my own body. Need not further proof in that moment of my total unenlightenment.

It’s everything that comes after the burning sensation that constitutes unnecessary suffering, says Vipassana — that we’re always manufacturing more in the mind than exists in reality. Life-long conditioning of craving and aversion impose a sort of “gravitational weight” on how the mind responds, creating tiny “loops” of ever-building suffering until the energy of the thing burns out. And so, the wise intervention is to cancel these responses altogether and, instead, welcome all passing sensations (and pass they reliably will!) with a calm, peaceful, grounded equanimity: the achilles heel of unnecessary suffering.

The effect this has on the UOSR appears to be one of total system equilibrium. By meeting the mind’s reflexes with equanimity instead of our usual responses, we’re effectively weakening their ability to assert themselves. And so, the idea is (ostensibly), if this were to settle in the mind as a habit, equanimity would naturally arise as an unconscious instinct to fully characterize the quality of our responses.

Because UOSRs, when strung together like links on a chain, are the summation of one's whole subjective life experience, we can imagine the implications.

This is serious and counterintuitive work! And decidedly NOT easy. It’s a true slog, the meeting of pain, anger, moments of calm, or a jacuzzi of warm bodily tingling alike, all with this continuous posture of non-indulgence. Even the task to deploy equanimity itself became a trigger for craving and aversion. Eck, the guy next to me hasn’t showered in four days and so I am meditating on his stench. Let me just kvetch, would ya!?

As I got the hang of things, I felt directly how craving and aversion lost the inertia to yank me into suffering. Equanimity had this growing resistance on them — like trying to move fast through water, their agility was now subverted and smoothed. When I’d trip up on a UOSR (inevitably) and respond in my usual ways, I’d just begin again. But a residue of clarity would remain that built up over time to what I am palpably certain of today: I am the author of my own suffering.

A walk down any city block the world over will demonstrate the scarcity of this knowledge. But it’s certainly not an original discovery. Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens and popular intellectual, is a long-time student and occasional teacher of Vipassana at Dhamma Pamoda, the same meditation center I attended in Israel. Harari first went on retreat in the early 2000s while doing his PhD at Oxford and said it was the most important thing he’d ever done. He now blocks 60 (60!) consecutive days a year for retreat and credits a lot of his work to his quality of attention and self-understanding.

“The most important thing I realized was that the deep source of my suffering is in the patterns of my own mind. When I want something and it doesn't happen, my mind reacts by generating suffering. Suffering is not an objective condition in the outside world. It is a mental reaction generated by my own mind.”

A whole, new world

The same bells that rang to wake us each morning rang too at the end of every meditation. Some folks would bolt to the door and out of the hall, so as to be first in line for food, their cushions and blankets left disheveled. The rest of us would rise slowly and arrange our space with care.

Why rush, I thought. To what end? To feel rushed was pointless when nothing and nowhere beyond the retreat grounds awaited us when we were done eating. Anything and anywhere was nowhere but there.

And this is what retreat is really about. It’s not merely to “pay your dues” for eleven hours in the hall. It’s to recognize that there is no boundary between formal meditation and the rest of life, that anything – everything – is a meditation. And so it became.

When I’m out in the world now and notice a tree, what I see is an anthropomorphic lank with a sense of humor. And when they’re grouped together in a light breeze, forget about it, I’m chuckling.

This all dawned on me a few days into retreat while sitting in a white plastic chair on the patio outside my room before a grove of eucalyptus. They danced so goofily in the summer winds of northern Israel, I might as well have been at a matinee comedy show — a gangly, swaying entourage of leafy branches at the crown howled weeeee in something like native Trebrew (?), their expressive language of an honest thrill. When a big gust came, they’d all flail wildly like those well-timed photographs of a family free-falling down the vertical track of a log flume at Six Flags. There’s nothing else to say: for me this was a belly-laughing, boyish joy.

I’d have other moments of deep presence alike or perform dozens of unique actions that became meditations, too.

Lift the left leg, lean forward, place the foot, apply weight, lift the right leg, swing forward, land the foot, apply weight. All lightly, light as air, silent as space, a whispering stride.

That chameleon, frozen and perched on a rock, is it preying on a bug? A beetle in the grass, perhaps? I can’t believe how still it is, a camouflage strategy? Come on, little guy, do something already. Hang on, is it a chameleon statue? Can’t be. Wait, it moved. Did it move?

Clink, clink-clank, clank, clank. The percussive echo of a fork symphony in the dining hall articulating our shared silence. Background music to the flesh of this apple glistening in the golden hour sun, like a crystal city of sweet joy. My bite marks on the skin, a perforated dental fingerprint.

Hoooly shit, this ant superhighway stretches two dozen yards, thousands of critters crittering, same place, same time, every day. Hauling leaves and dead grass in the scorching summer sun, making tiny collisions with each other, feelers feeling feelers for right of way, the rules of the road, tumbling down a network of underground tunnels, a queen – worshipped, no doubt – on her tiny dirt throne six feet under. What are their systems for colony-wide communication? Do they have meetings, street signs, laws? What intelligent coordination!

It was as if I was plopped on this magnificent planet from a dull, dim, bore of a place in some forgotten corner of the universe. Earth had a new glow, a level of detail and beauty expressed on their own terms, with the open arms of an attention fit to receive them. And my response, a rush of love, of gratitude, of awe for the mere fact I could bear witness to it all. I was alive as a human with the cosmic gift of consciousness. This is how I wanted to be in the world.

On the tenth day we were allowed to speak and mingle. It felt like the last day of high school — we came of age, we’d bid adieu. Doctors, professors, students, artists, tech professionals, baristas, teachers and parents. We swapped stories we’d invented about each other, personalities “extracted” from the silent actions of contemplative creatures.

A ride back to Tel Aviv with three young guys was on offer. I thought of Noa and remembered all that was said on the ride up from Jerusalem about retreat, about life. How it felt to be in her presence, one who moves through the world with such grace. Each day of retreat when I entered the hall or rose to leave, I’d notice her. There she was, always on her cushion, never rising, a lotus pose in perfect stillness, an inspiration, suffering in peace. I thought of her kids and her husband and her life back in Jerusalem. Wondered what these ten days might mean for her as mother, wife, woman, human.

Just as I went to look for her, there she was across the room, walking toward the front door. As she pushed it open to leave, she looked my way and paused in step, smiling. I slid my chair out to stand up and walk over, but was stopped by her gaze. What needed to be shared was exchanged in that silence, and in the long silence of retreat. So I sat down and with a full heart, looked at her – paying attention – and smiled back.

Noted

[1] The organization that facilitated my retreat: “recognizes this doesn’t work for everyone and that sometimes members of the LGBTQ+ community may not feel comfortable on either side of the campus, or having to identify as male or female. If conforming to binary gender separation is a concern for you, please let us know when you apply to the course so that we can try to arrange a space for you where you can feel safe and not distracted while you meditate.” Note: not all Vipassana retreat facilitators separate by gender. ↵

[2] There are many schools of thought and types of meditation. This is just my layman definition. ↵

[3]. Getting here in meditation practice is a process whereby one experientially isolates the perceptual layers and false postures one has of any given "object". For example, if one was asked to pay attention to the sensations in one's face, a lot is happening simultaneously beyond the "obvious". (Sensations – pressure or tingling or temperature in what feels like a mold of your face shape; Concepts – a mental image of your face; Location – your face appears to be located “above” your chest or your sit bones; “The Meditator” – Who, or what, is paying attention to your face?) The “sum” of these qualities make up a cohesive interpretation of experience when not paying close enough attention to individuate them. ↵

[4]. While equanimity and happiness are not identical (and we lack the technology for a real-time biometric emotional analysis), the 2020 World Happiness Report (embedded below, fun to play with) can be something of a corrolary. In the US, UK, and Europe, folks feel that on a 10-point scale that measures the best possible life for themselves, theirs are averaging ~6.5/10. ↵

[5]. Note: not all Vipassana retreats are Goenkian, nor do I subscribe to the idea that a Vipassana retreat must be. I also can’t speak for the retreat experience beyond my own, of course. ↵

[6]. However, one might notice craving can arise in the presence of “negative” sensations as well. For example, if one is grieving a recent break-up, they might “escape” to loving memories of their ex, flooding their system with “positive” sensations to thwart the pain of the reality. But ultimately, beneath that coping mechanism, is one’s aversion to the pain. Hot take: this is the fertile psychological soil from which addiction springs. ↵

This essay originally appeared in Leeway. Thoughts? E-mail me@michaelsaltzman.com.