[M7] What Would You Do For A Klondike Bar?

They wouldn’t stop staring. Time would pass—I’d gaze out the window, jot down a note, follow the second hand of my watch as it swept around the dial, and run my fingers along the worn, lumpish texture of the booth’s patent blue leather seats.

I’d look up. Again, invariably, staring. But it wasn’t always the same one. It was a tag team effort, a staring post—someone always had to keep watch.

A photographer who shoots life as it happens is stymied by a subject who becomes aware of the camera. Once it’s clocked, the truth of that moment is lost and the camera becomes like a glock revealed in a negotiation between criminals. Occasionally there is intrigue, but mostly it symbolizes threat, implies mockery, violates privacy. The Mennonites no doubt stared under this presumption, but the camera and the hands that hold it wish to tell honest stories of our humanity.

The staring began to feel excessive, so I thought: Alright, I’ll play, and stared back. There were nine—two men and a gaggle of children, four boys and four girls. The gals were bespectacled in thin oval frames, white or black coifs, and shoulder-padded, loose indigo or grey dresses brushing the floor. And all the males adorned with bowl cuts, scraggly beards, charcoal wool trousers with criss-crossing leather suspenders, and band-collar oxfords of indigo, cyan, seafoam, or chambray.

But then I looked closer and what I saw was a family—two brothers whose faces you could see in the children they’ve fathered. There was something animalistic about how they cared for their young, fed their young, protected their young, how those kids only moved about the train in flock, how the staring may not have been merely vigilance but some earnest curiosity of other.

The cultural divide in the car was palpable, and in a way the camera became a bridge. One of the brothers, Joel – I have to suspect – noticed what I was trying to do by doing the same: he looked past what he saw, past himself, and toward my pith. “That’s a nice camera,” he said, breaking the impasse, and held up his point-and-shoot in comparison. “Probably takes better pictures than this.” I was taken aback by such a normal comment and how he went right to the heart of the thing. I tittered, like we had an inside joke, and glanced at his brother, arms around one of the boys peering out the window together. I jerked my head up at them as to point: “Great idea to bring the binoculars.” And just like that, other collapsed.

He asked that I join his booth, introduced me to the kids, to his brother, to his life on the Pennsylvania farmlands, and to their love of Amtrak railroading, their community of which has heartily embraced to move about and see the country. While they have more of a relationship to modernity and technology than the Amish, to be near-at-hand with Mennonites is nonetheless a collision with 16th century life. And for them, on the train, a collision with the 21st. In the Sightseer time travelers meet.

Living in a noisy world encourages you to speak over it, to speak over yourself. But the Mennonites were soft spoken, whisperers even, a reflection of the world they come from. The conversations amongst themselves imperceptible even in the quietude of the Sightseer at close range. Their bodies spoke softly, too. Soft in stillness, soft in movement, each gesture careful and considerate of its surroundings. They moved at the pace of nature, like trees that sway in the breeze.

Joel was a delight to engage with, grace embodied. The children watched our conversation, watched their Father, their Uncle, with great curiosity. One by one they modeled him, came closer, surrounded me, took interest, looked me over, abandoned fear. Had they never been so close to someone from the outside?

He asked if I were ever in Pennsylvania would I come to visit them. “I’d love to take you on a horse and buggy ride.” He slid his card with an illustration of a stallion across the table: Rock Oak Farm, Sale Prepping and Training. “I’d love to have you stop by,” said with a gentle charm, smiling with his eyes.

The other folks in the car were in disbelief, still in their posture of judgment, just how I was moments earlier. I offered my name and email wondering if I should brush up on my Pennsylvania Dutch as a potential community recruit. But no sales calls thus far.

The train slowed and the conductor announced we’d have a fifteen minute fresh air / smoke stop. As Joel got off with the kids, he asked if I needed anything from the store. “No, my friend, thank you,” pausing from writing to answer, thinking nothing of it beyond my own discomfort with accepting a kind offer.

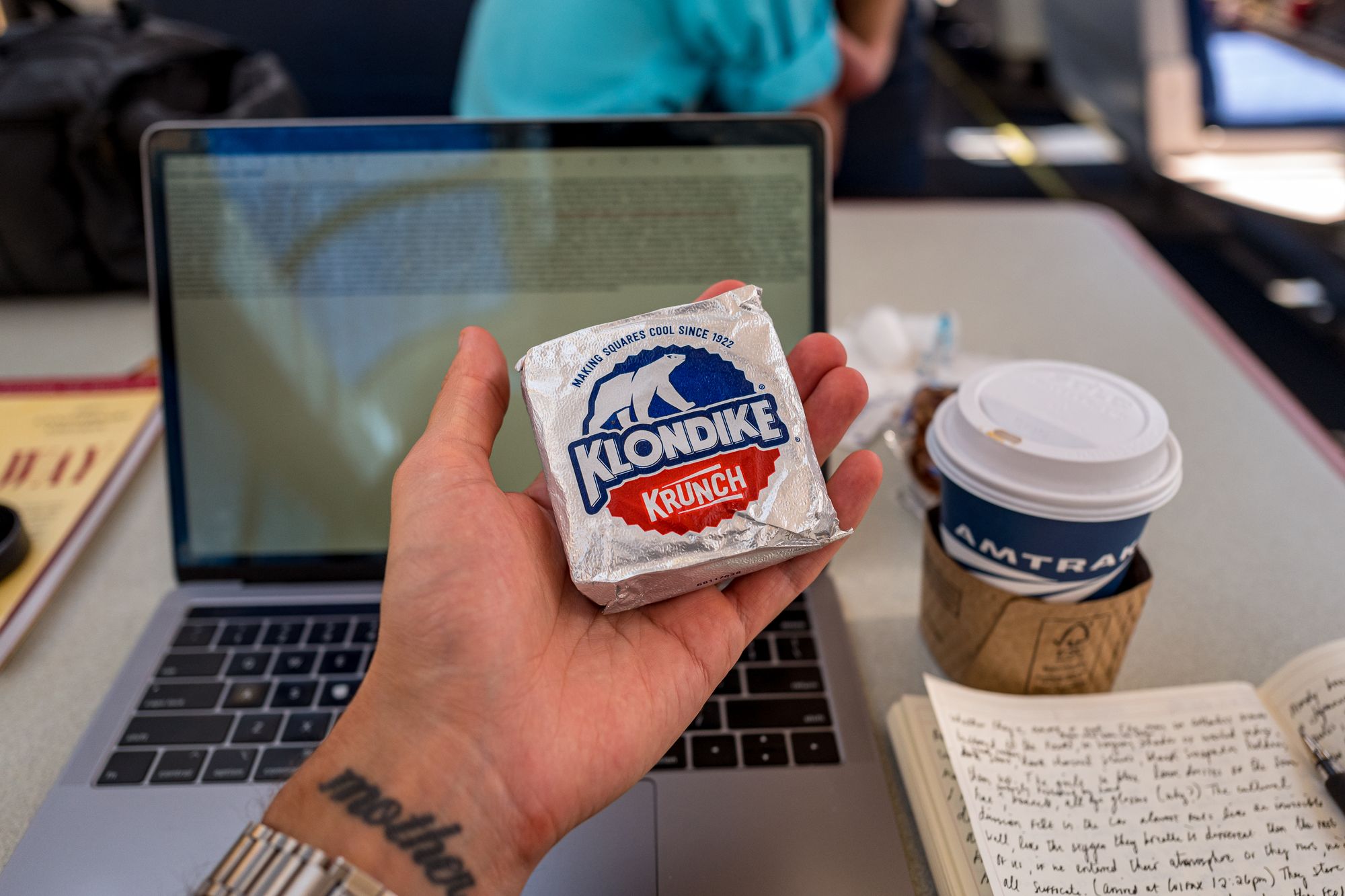

Ten minutes later, the family flowed back in, the girls squeezing into the adjacent booth and the boys perched on a row of seating in front of me parallel to the windows. Joel followed and leaned over the backrest of the girl’s booth, handing them each a Klondike bar, and then over to the boys, too. He turned to my booth, looked at me, and extended his hand.

I can’t touch with words the generosity that emanated from such a simple gesture, but I was moved beyond measure, like he had just adopted me as one of his own. And immediately after, tickled by the comedic value: A Mennonite man bought me a Klondike bar.

There is a last time we'll do everything—our last car ride, last coffee, a last kiss, a last breath. This was the last time that will happen to me, I’m sure of it. So in a bizarre twist of humor and the sacred, along with Joel's children, nieces, and nephews, I indulged in total bliss. And knew whatever they were wearing, whatever their beliefs, whatever their way of life, and whatever mine, that sweet, creamy, nostyglic ice cream novelty was making us all feel just the same.

Next, on Moved